The primary innovation in this design process is in its scalability. Too many authors claim scalability but don't show it or explain it. This approach is different because it comes from many perspetives.

Part 4: Timeless-ness and its Origins

"The world is complex, and so too must be the activities that we perform. But that doesn't mean that we must live in continual frustration. No. The whole point of human-centered design is to tame complexity, to turn what would appear to be a complicated tool into one that fits the task, that is understandable, usable, enjoyable." - Don Norman

The primary innovation in this design process, is in its scalability. Too many authors claim scalability but don’t show it or explain it. This approach is different because it comes from many perspectives. This process synthesizes both my design studies from many wise authors, through conversations with leading designers at UX conferences, and the work practice and mentorship from many of my brilliant colleagues, in addition to my own practice and the practices shared with me on the long journey that has been my multi-domain career in design. (See a partial list in both references and acknowledgement sections at the end.)

In so doing, I learned first-hand what worked and what did not. And what no one has done in design processes I have known is to separate the method or technique from the process, specifically for software projects, and that is the core of this scalable design process: be guided by the process goals not a particular unscalable method or activity. A sharp designer will know how to analyze a context to pick the method or technique that will best achieve the design goals in a given context. (And indeed, Keen consulting often assists companies to learn that analysis either for a specific project or for a company or organization.)

In my previous article, Part 3, I detailed the Timeless Scalable Design Process, presenting a structured yet flexible framework that balances creative freedom with methodical progression. This “controlled random walk” approach allows for innovation not just within a structured framework, but also by forcing the designer to be confronted with uncomfortable and uneasy issues and requiring designers to use their critical thinking skills. Less professional designers and design managers have criticized this for “head exploding” complexity, which is more an admission of the modest capacity of their design thinking than a critique on how simple design ought to be. In many ways, a true design process separates a true designer from a carbon version of an AI machine. The results from a design process will deliver designs that are both innovative and durable which a commodity design exercise can never do. [On a side note, a question for the AI specialists in the audience: is it true that AI can only deliver conservative results because it uses an LLM which by its very nature is rooted in what has already been done and what is currently possible (in other words can AI synthesize but not innovate)?]

A proper design process may take longer to produce an initial deliverable but ultimately yields innovative, more consistent, and more durable designs than ad-hoc approaches, which will eventually result in a “Frankenstein's monster” of design workarounds and inconsistencies that results from ad hoc design.

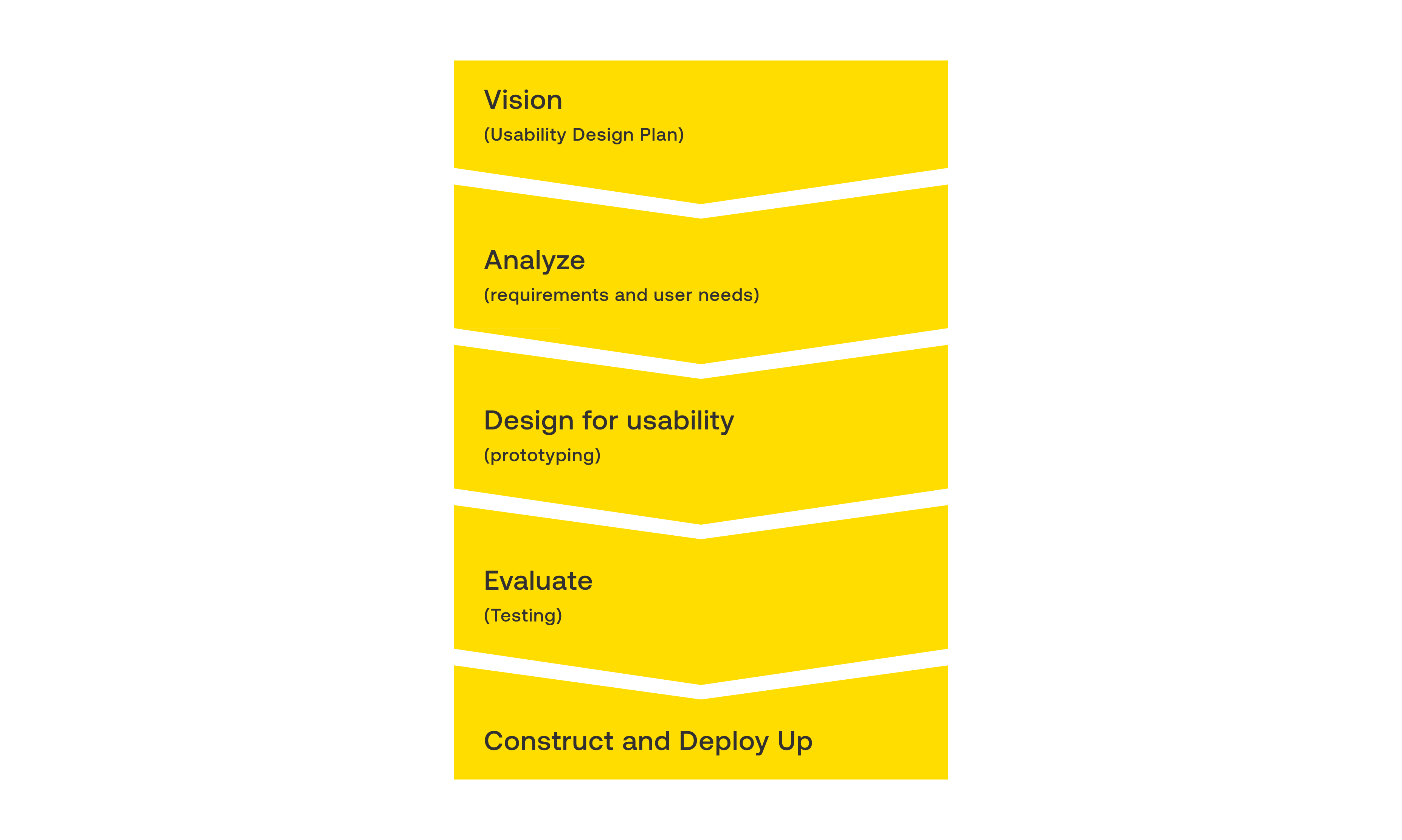

The four-phase process below flows from a concrete starting point, called the “existing state” to the more elusive “preferred state.” The preferred state is elusive due to its indeterminate state. In an earlier age, like when Herbert Simon first coined the term, “preferred outcomes,” design had a definite end. But now we find ourselves in an age better described by Horst von Rittel, where the design project ends “not for reasons inherent in the logic of the problem. Instead, we stop for considerations that are external to the problem: they run out of time, or money, or patience. Finally we say, ‘That’s good enough,’ or ‘This is the best I can do with in the limitations of the project’ or ‘I like this solution,’” etc. The four phases in between those two states are:

- Discover: This phase begins with first understanding the design challenge and then expanding and reframing the issue. Using critical- and systems- thinking interactively with stakeholders, they reframe the problem to gain a holistic understanding before converging on a definition that will govern the project.

- Concept: Formative research combined with critical thinking establishes the foundation for 3-10 unique conceptual solutions. Through iterative design and formative-evaluative research, these concepts are synthesized into a single conceptual model that directs the rest of the project.

- Detail: Via more evaluative research, the conceptual design is translated into a concrete design. Design also coordinates with engineering resources for implementation and design asset. The detailed designs are validated through user research, eventually converging into interaction patterns, building blocks, and other design elements.

- Deliver: Often starting as the “Devil is in the details” phase due to unanticipated issues that arise during implementation, this phase requires close coordination with development to solve problems while maintaining conceptual integrity. By the end, it becomes the “God is in the details” phase as the envisioned user experience takes shape.

Timeless

As mentioned above, what makes this process scalable is its emphasis on universal goals per phase rather than specific activities or methods. By separating activities from the design goals, this allows designers to tailor their approach to the project’s scope, resources, and their own expertise while still meeting the timeless goals of each phase. But the steps themselves are essential to this process and the questions arises where did they come from, since I did not just make them up, but rather stand atop some very tall shoulders.

Where did the process come from?

A simple answer: this process came from a synthesis of the design processes I and my many colleagues have practiced; from the design theory I have put into use and from the many other designers who have helped comment and refine this process (see the list of references and acknowledgements at the end for a sizable, if incomplete, list). As mentioned above, of particular importance was also the study of many design processes from leading designers, design schools and design movements.

What did all of these processes and theories have in common? It certainly was not the methods, nor the techniques utilized. For those activities, there was little agreement. But there were still many lessons to be learned, which I will share with you below.

What is the design process? and where did it come from? A complete history of design involving the Discover-Define-Develop-Deliver (the terms employed by the most common versions of the double diamond) method would take easily a tome way larger than we can cover here. For our purposes, I am just going to give a brief summary (and my apologies for those lovers of the history of design who will see this as an over-simplification) via a few examples of early and formative versions of the design process and its steps. In these examples, these terms may seem to vary greatly but as design practice becomes more and more experienced, we get more and more refined and distilled themes and variations to the point we can synthesize the steps as described below.

Early pioneers

Our journey must find some starting place so in the interests of time, I’ll begin with one of the first design processes and an understanding of design we would recognize. László Moholy-Nagy, who started his career in the Bauhaus School, best articulated his design process in his work done at the Chicago Institute of Design, that would later be known as the Institute of Design at Illinois Institute of Technology. But he started much earlier in the Bauhaus school in Weimar, Germany. At the Bauhaus, and other roughly contemporaneous design movements (constructivism, Deutsche Werk bund, etc.), a standard approach to design developed that could be summed up—generally—as “form follows function,” meaning that the form should be dictated by an object’s function. In Chicago, Moholy-Nagy augments this concept, “the statement, ‘form follows function’, has to be supplemented; that is, form also follows—or at least it should follow—existing scientific technical and artistic developments. including sociology and economy.” In so doing the design process acknowledges a world outside of just the form and function, encompassing both a broader context including aesthetics. To this he encapsulated a design process. One can distill Moholoy-Nagy’s process as follows:

These steps correlate roughly to our Discover-Concept-Detail-Deliver.

Discover – Investigation

Define – Ideation

Detail – Experimentation

Deliver – Realization

Since then, iterations of this approach to design have surfaced, with this common theme in some form or other, here is just a sampling.

Academic attempts: Brian Archer

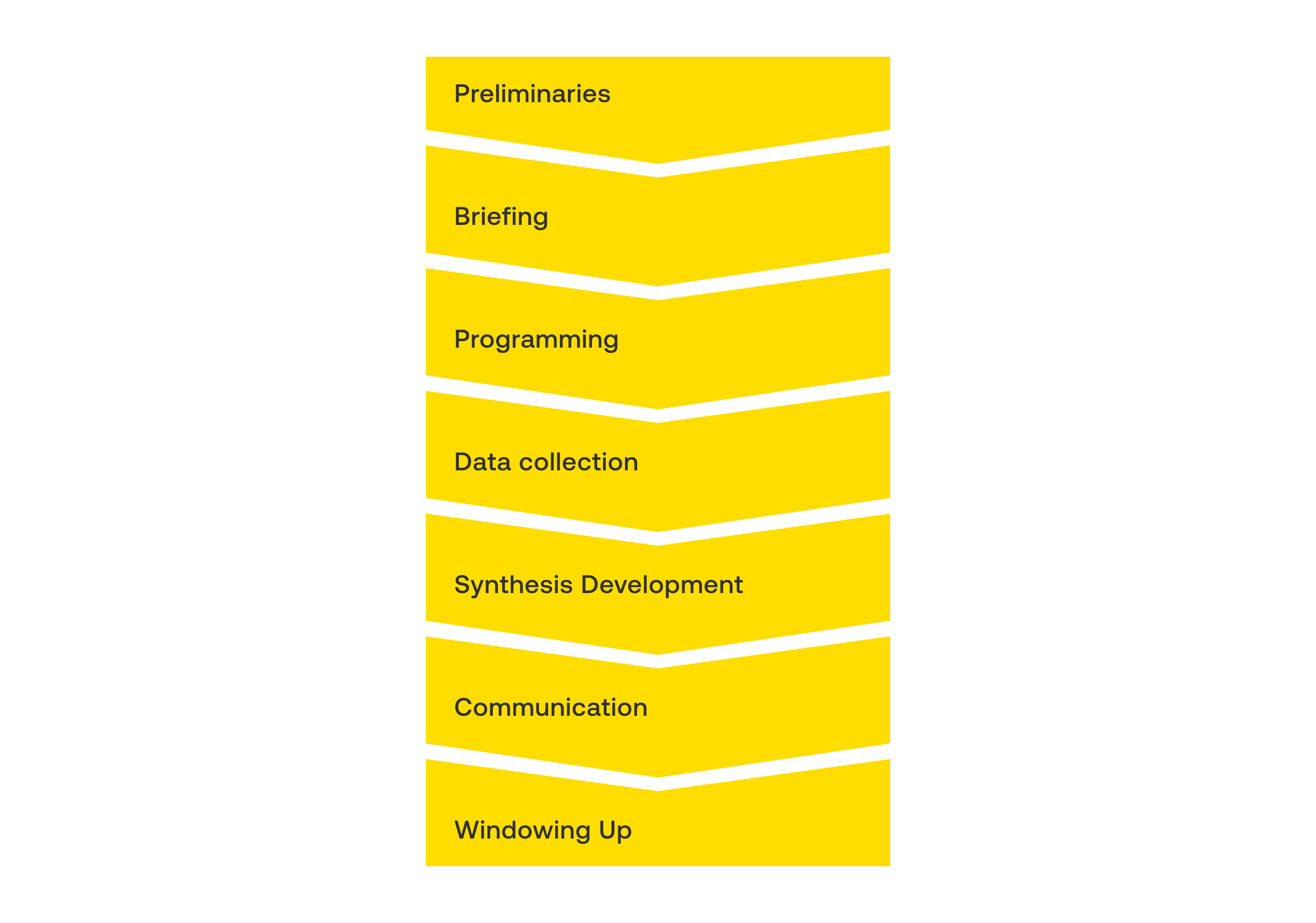

Brian Archer’s systematic design methodology specified the process into a kind of cookbook or checklist that attempts to capture all permutations of a design project. The exercise encumbered over 250 steps, but they fit into roughly 7 phases:

If we were to study the definitions of these phases they could, likewise, be condensed easily into the distinct four phases:

Discover – Preliminaries & briefing

Concept – programming & data collection

Detail – Synthesis

Deliver – Communication

HCI Engineering Processes

In parallel with the design community, the HCI community followed its own course. The HCI community was known by two similar names: the CHI (Computer-Human Interaction community) which was the academic community associated with ACM/SIGCHI or the HCI (Human-Computer Interaction community) associated with the academic discipline in general. These groups were largely interchangeable depending on who you thought should go first, the computer or the human. But the flagship conference for UX design in the 80’s and 90’s was the CHI Conferences (and other specialist UX conferences) sponsored by ACM/SIGCHI. At these conferences meeting other UX design practitioners was a place for sharing and developing HCI work.

This community followed its own UX design processes, in isolation of what was happening elsewhere in the field of design. Their approach more resembled an engineering approach. Indeed, during the 1980’s and 1990’s many HCI practitioners referred to themselves as “Usability Engineers.” There also developed a cottage industry of Usability Engineering Consultants that could help software companies create easier to use software, since there was no one in-house who could perform that function. These early HCI professionals were certainly more in-line with the old Bauhaus of form follows function with very little regard to aesthetics, except for one of IBM’s old favorite mantras: Keep It Simple Stupid.

Unified Software Development Process

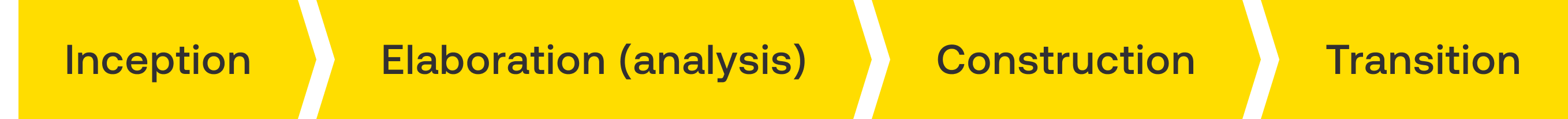

Just like today, where design seems dominated, if not subjugated, by Agile software engineering, so were the 80’s and 90’s dominated by another software development process, called the Unified Software Development Process. It was extremely influential, since it was a given that Usability Engineering needed to follow the engineering process of the day. The Unified Software Development Process was a waterfall method. At the time, the Unified Software Development process looked like this:

These steps followed a purely engineering process where Inception was the beginning, starting with a first meeting of the software team with an initial “iteration” and after some analysis a second iteration is produced which would be the basis for the next step. Elaboration then would take the second iteration and extrapolate requirements and a further analysis which would end with the start of what they call 'design’. Then in construction the software was created and tested, that was then the end of design. The process concluded with the Transition phase which was the deployment of this software. This transition was also referred to as “Iterations 3+,” think of these “iterations” as versions of software where the entire process is not repeated but added to: new features or bug fixes.

HCI professional attempted to force fit design activities into this (and other) Software Engineering waterfall process.

The Unified Software Development Process put its emphasis on a release of a single waterfall program that would then get iterated on in versions. It gave a definite end to the software project which would have made Herbert Simon and his design followers happy, had anyone cared (but they didn’t). Waterfall development processes were not going to survive as software became increasingly more and more complex so that the software took longer and longer to produce, resulting in the need for earlier feedback. This need gave rise to the now ubiquitous incremental Agile development methods.

User Centered Design

As the design in HCI also matured so did the design processes. Specifically, the HCI community differentiated itself as the ones who “advocated for the user” in the form of user-centered design. Various flavors of the user-centered design process started popping up especially in workshops at various HCI conferences, such as his one from J. Gulliksen, who attempted to teach user-centered design to HCI professionals. Gullicksen’s process mapped to the Unified Software Development Process software engineering processes, not to the design processes of people like Laszlo Moholy-Nagy or Brian Archer.

These HCI-based processes had simplified views of the place of design in software projects. Notably missing is an explicit Discovery phase as it just accepts a design brief as it is given to them and immediately proceeded to come up with a detailed UX plan (which was thought to be universal to the development process) and then analyze user needs and requirements in formative user research resulting in the closest thing to a concept, though it is not referred to as one. Design for usability is the detail phase combined with evaluation, which from early on shows up at the end of the process.

Influence of Other Disciplines

As the HCI community grew it came into contact with other similar professionals like architecture, anthropology and even design. Aspects from these other disciplines began to rub off of each other in terms of methods and techniques and sometimes even processes. For example, the design community originally came up with the concept of design rationale, from the work of Horst von Rittel. But the CHI community quickly championed this and the most recent works on design rationale are usually from the CHI community. The fact that half the readers are now scratching their heads is testament to how little a role design rationale plays in many UX projects, despite being an essential aspect.

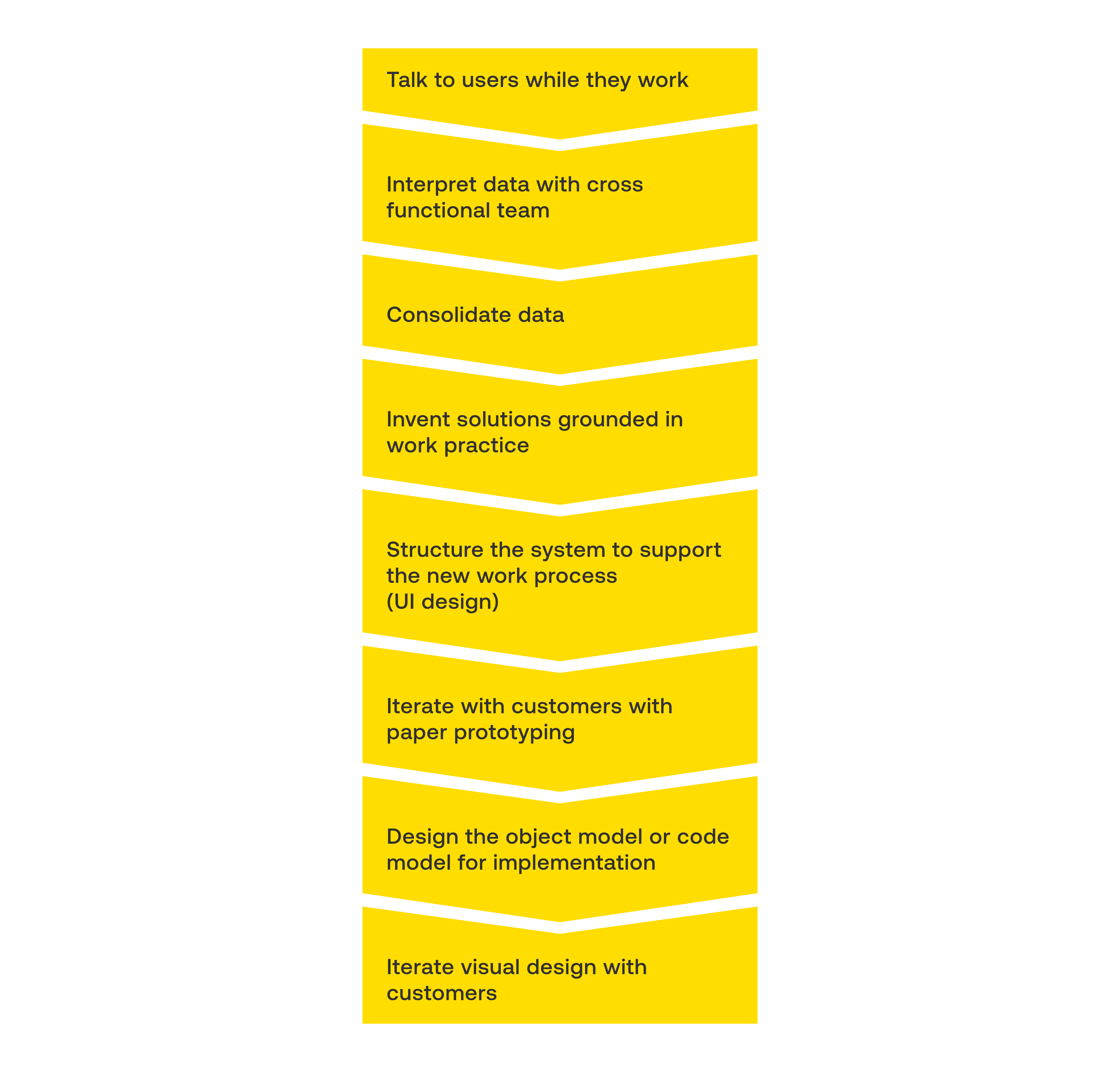

Many designers like Karen Holtzblatt (who ran a very successful Usability consultancy) took a popularized version of anthropology, creatively applying simplified in situ research and applying it to HCI engineering. Holtzblatt’s particular approach is called contextual design. This process also developed around the time of a growth of a new breed of HCI consultants to help software companies with no in house designers. Therefore, the design work was front loaded into the project, the work was delivered and usually the consultants were rarely around for the development phase and could not see the results of their work. This version of Contextual Design took a formula or cookbook approach to how a user-centered design process should be conducted with required steps and deliverables. It also clearly included the idea of iterative design, showing an increasing awareness of the outside design community. The original version (modernized ones have since evolved) of Contextual Design followed these steps:

This process attempts to assert, independent of engineering, a process to come up with a user-centered design that is only designed to take an approach that questioned the product from a user’s perspective. The phases are descriptive and an example of a cookbook approach that should, according to the author, always result in a successful user-centered design.

The first 2 steps correlate to the Discovery process, but only as it relates to getting user’s needs and feedback. There is no reframing the problem or any other major design thinking. This is still rooted in delivering design assets to development based on stated needs and then adding user input. This really isn’t a design process either, as the design community would understand it. The next 2 steps relate to the Define phase but with prescribed activities, like paper prototyping. The define phase as designers understood it then, followed the practices of design theorists like Donald Schon, where there was much more an emphasis on design reflection and conversational generative design with stakeholders (usually clients and others but not necessarily the users). As one graphic designer, anno 1994, once proudly told me “we don’t need user input, whoever usability tests a brochure?”

The last two phases in Contextual Design appear when the design work is done and ready to be delivered for development. It was then that visual design (which was looked upon as a separate unrelated design aspect). was added independently to the final product.

Coming closer to the user: Scenario Centered Design

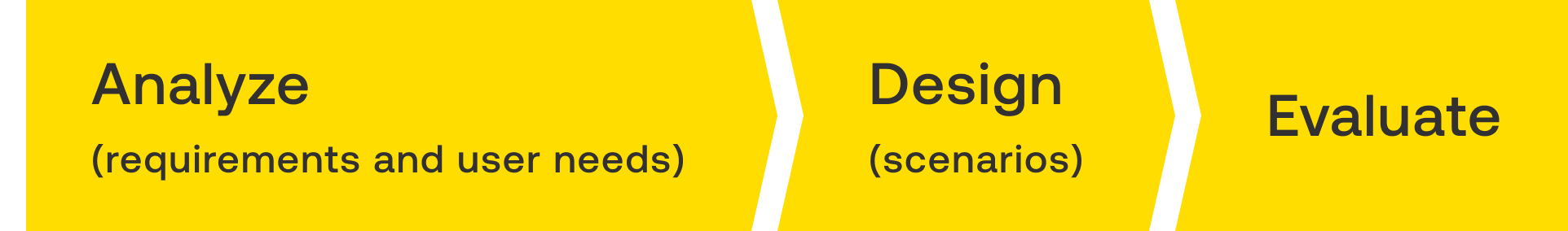

Other variations on HCI user-centered design started cropping up in attempts to get closer to the user. One of the more interesting and durable approaches from among the many that cropped up, was called “Scenario Based design” by Mary Beth Rosson and John Carroll. In this approach, end user scenarios came out of user interviews reflecting how the users work and conceive of their work and resulted in scenarios of workflow and task analysis for guiding design. Their original process followed this structure:

Like Holtzblatt this process also has no direct connection with development as after Evaluate development takes over. The design exploration is also limited to the scenarios which are then translated into wireframes.

Usability Engineering

Deborah Mayhew’s process was a big leap toward a more design-like process (despite its very engineering-driven structure). She also introduces the concept of iteration into what she called The Usability Engineering Life Cycle. That cycle used these steps:

The conceptual model is, for the first time, explicitly incorporated into design and instead of going for sequential steps, Mayhew’s process puts the accent on the iterative nature of what she calls Usability Engineering. Here testing is also called out late in the process but its iterative with screen designs and more closely maps to the detail design in our design process. Mayhew’s efforts are firsts steps of how HCI and Design will begin to converge. The design and the HCI community began to struggle for the same turf of designing software: one had the superior processes, the other the superior methods. As each began to recognize this, both disciplines started borrowing from the other. You had schools like Carnegie Melon University that had both a Design school and a separate Computer Science department, with both of them granting degrees in UX design (though they were not called that at the time).

Eventually, designers developed user-centered design envy and HCI people developed designer envy and that’s how design thinking was born, an area dominated to this day by non-designers who think like anyone but a designer. And that brings us to …

Commodity Popularizations

This is the start of what should have been a high point in design, especially the design institution in business (what is badly needed, even to this day). Instead, we have a situation now where the design process is often paid lip service to but plays little actual role in the software design process. How did that come about after these promising starts?

One major factor is since engineering does not have the patience nor the understanding of the holistic design process, the idea was to incorporate the business side of software into the software creation process. This bode well because the design community was, at that point, more comfortable working with business and the HCI community more comfortable working with engineering. Business Strategist Roger Martin, then the head of the Rotman School of Design attempted to introduce design as a key element of business. He was not successful, instead attempts by non-designers to snatch the idea, oversimplify and commoditize it started a trend in UX design which was essentially stripping design of its professional standards as design practice became separated from design foundations. This started the wild growth of “we’ll train you in a workshop how to be a UX design professional.” And just as they were doomed to failure when done by design agencies, they were even more of a disaster when done by online bootcamps.

There were valiant attempts to infuse design into HCI, these were designer tracks designed to create a design rigor along with HCI academic rigor. Gerrit van der Veer, Wendy Mackay, Boyd de Groot, Marilyn Tremaine, many others and I tried to get CHI to take design seriously.

Meanwhile, on the design side similar efforts were afoot. Together with Elizabeth Dykstra-Erickson (and later Richard Anderson) we reached out to the AIGA, the American Institute of Graphic Artists. Rick Grefe, then the president of the institute saw the importance of a combined effort of HCI and Design and together with the ACM/SIGCHI sponsored joint summits, culminating in the AIGA (Terry Swack and John Zapolski) with the ACM/SIGCHI (Myself and Richard Anderson) presenting the DUX conference series in 2003 and 2005. However, like CHI, these efforts stranded after changes in leadership at both the AIGA and ACM/SIGCHI resulted in both groups becoming more and more insular and less relevant.

At that time, it left a situation where no one was minding the design store. HCI curricula, at the time especially, had stranded. One found good HCI design educations hidden in places, like the School of Library Sciences at the University of Michigan and did not find it in places you would expect: RISD or Parsons, or many leading computer science departments.

There was no clear UX specialty in the early days. So very often, unsuccessful engineers or people from other disciplines started taking up the design tasks at many software companies. The result was software companies often had relatively untrained “designers” who had non-design backgrounds; but when real designers were hired they lacked the seniority that these untrained UX people had. As UX grew in importance, the “senior” non-designers rose to the top of UX management with disastrous results for the design process. People with no design background became responsible for managing those who did. Things like a design process were scuttled as they were mistakenly thought to slow things down. This put designers on the defensive and fell back on the only process they did see: how to please engineering-driven decision makers. To this day there are people with no understanding of design processes leading design in large companies, and it’s little wonder their teams are getting laid off and get replaced by commoditized designers.

That is not to say that design processes were completely dead. Individual teams with more visionary leadership did deploy professional design processes and their product flourished like an island among a sea of software. There was also Design Thinking, which was ready to re-inject at least a starter’s design sensibility into software creation.

Design Thinking as it is generally practiced, is not strictly speaking a design process as this new process was repackaged to be compatible with—and this will surprise you no doubt—existing engineering practices. Practices which by this time had converted to Agile with an even smaller appetite for design than waterfall had. And the results are the over-simplification and dumbing down of the design thinking process.

Design Thinking

Since HCI professionals and software engineers were usually not trained in design, designing or design processes, there started the Design Thinking movement which commoditized the process into something simple and sellable. These non-design trained professionals offered a simplified version of the design process, that catered to their simpler understanding of how design works.

Its utilization was a successful way to introduce design into companies that were new to design. They wanted a simple and easy to understand design method that produced quick results that were an improvement over their processes (that did not use design thinking of any flavor). In this way, design thinking was a good tool to introduce design to new companies who are not ready for a fuller design engagement. For example, you want multiple iterations or ideas? Design thinking processes will give them to you, if they fit on post-it note. Okay, that’s not completely fair, there are many practitioners of design thinking that thoughtfully try to integrate design processes, as we shall see below. But still, a majority of these efforts emphasized a quick and uncomplicated process. These processes were more meant to clarify product thinking than to truly facilitate the critical and systems thinking that a true designer would bring into a software project.

The reader will not be surprised that most of these design thinking processes, like most early HCI process, were meant to be front-loaded into the software engineering process and barely interact with it. Moreover, many companies utilize these design thinking sessions as if it were a substitute, not an introduction to real design thinking. That had the negative effect of this emerging design process being siloed and while useful with fleshing out an existing product idea, it did not have the critical thinking to challenge that initial definition nor the carryover design processes to actually realize the product definition effectively.

Attempts at Design Thinking process codification

The Interaction Design Foundation captures the canonical commoditized design thinking process. The positive step here is the more prescriptive steps of previous HCI processes are getting replaced with more goal-oriented descriptions, that harken back to the design processes discussed earlier.

This process looks comprehensive, but it isn’t. Nor is it a reflection of the way a designer thinks. Instead, it is a series of shortened and simplified design steps. These steps do not scale, for example, a large and hard to reach user population knocks this process off its stride at the very beginning.

These series of steps are a rapid process conducted in serial fashion. The definition of the steps is narrow. For example, the research phase is aimed at empathy (a mantra in design thinking) but it’s a quick and over-simplified version of what Holtzblatt already covers in her contextual design. From there the steps flow into one another and in the end is a prototype that has been evaluated (with usually predictable success). One can argue this formula approach of design thinking confounds the very purpose of design thinking: to go outside the box and look at multiple perspectives and discover a problem space that does not live in a user-centric world but rather an eco-system that includes users, customers, business, the market, society, etc.

"Design Thinking" for Designing in Agile

The Google Design Sprint also recommends phases, but it is similar to others that are variations on this theme. The Google Design Sprint book explicitly explains it isn’t a full software design method but rather an ideation tool, especially suited for start-ups and other blue-sky design projects. And that is why there is no attention to actual development as the prototype is a stand-alone proof of concept.

The Google Sprint method makes a valid attempt to miniaturize the design process for a specific limited purpose. For example, the first phase attempts to understand the problem space before going off doing stuff. I also like the integrity of this process in that it states what it is good for and that it is but a first iteration of a design process not its end. This entire sprint process could fit as an activity in a broader design process. The fact that some uncritical designers employ the design sprint instead of a design process short cuts design and not in the spirit of what a design sprint is supposed to be used for.

The following process is the Stanford Design School’s design thinking process written by Stanford archaeologist Michael Shanks.

Their process is almost identical to the IDF’s except instead of “Research” they call the first step, “Empathize.”

Like the IDF process above it is a shortened and simplified series design exercises that permit at least some reflection on the definition of a product. And in an environment where there would otherwise be no design activities, this process will give you at least some design input which could be better than none. I say could be because in its short cut methods it presents something as ‘complete’ when it is not. Moreover, there are still many professionally trained designers who have taken up the design thinking and using it to institute some higher level design reflection but adding more critical thinking and exploratory research to the design thinking agenda.

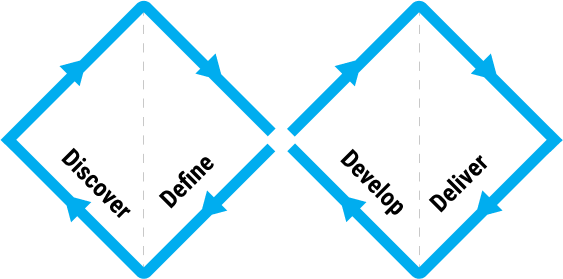

The Standardization of 4D Design

Finally, the classic source of the standardized 4-D process, namely the double diamond process, most famously popularized by the Design Council. No doubt many might comment that the double diamond process gives a more common recognizable view of the design method and normalized the usage of the 4D design process steps. This process leveraged, albeit vaguely, the best of the design processes with the user-centered HCI processes into a single process for the creation of well-designed software.

The double diamond, in its Design Council flavor looks like this:

The double diamond supports a pair of divergence and convergence thought process.

While many claim its visualization oversimplifies, the double diamond with its subtle usage of arrows does offer a convenient way to communicate design in succinct terms that intimates the messiness of design while reassuring the customer all will come out right at the end. In this way, the double diamond is not so much a ubiquitous design process as a ubiquitous design packaging. And in that it is very flexible and effective as it appears to speak simply the language of business in a designer’s jacket.

There are many more sources and many issues that have gone into our Timeless Scalable Design Process; but none, to my knowledge have so succinctly separated the goals from the activities so that the design process can scale to me the challenge of any size scope as we discussed in the previous blog posting.

The question arises how does this actually work in the wild. How can a design process such as we propose actually scale and in what ways. That is the subject of our next blog post. For now, below I will reprint a list of the references that have gone into the previous 4 blog posts, including this one. These are the references that have influenced and informed my design practice and this design process in particular. After that are a list of design professionals who have helped shape this approach to the design process, either directly or indirectly.

Now that we've covered timelessness and scalability, it's time to get from theory to application. We will be doing that in article 5, which is called "The Process in action".

References

- Alexander, C. Notes on the Synthesis of Form, 1964

- Archer, L. B. (1965). Systematic Method for Designers. The Design Council

- Beyer, H and Holtzblatt, K, Contextual Design: Defining Customer-Centered Systems (Interactive Technologies) Morgan Kaufmann 1997

- Cross, N. (2006). Designerly Ways of Knowing. Springer

- Deborah Mayhew, The Usability Engineering Lifecycle, A Practitioner's Handbook for User Interface Design, Morgan Kaufman, 1999

- Design Council (2012). Double Diamond. The Double Diamond by the Design Council is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/the-double-diamond

- Design Sprint Methodology, Google Design Spring Website accessed on 5 January 2025 at https://designsprintkit.withgoogle.com/methodology/overview

- Dubberly, H. (2024) “Conversations and models: Secrets to designing great products” https://presentations.dubberly.com/conversations_and_models.pdf

- Dubberly, H. (2025) “How do you design?” https://www.dubberly.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/06/ddo_designprocess.pdf

- Dubberly, H. (2025) “Why we should stop describing design as ‘problem-solving’” from Dubberly Design Office web site, https://www.dubberly.com/articles/why-we-should-stop-describing-design-as-problem-solving.html

- Eisermann, R. “The Double Diamond design process — still fit for purpose?” from Medium, accessed on 24 December 2024 at https://medium.com/design-council/the-double-diamond-design-process-still-fit-for-purpose-fc619bbd2ad3

- Esther Han, 4 Stages of Design thinking from Harvard Business School Online. Accessed on 3 January 2025 at https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/stages-of-design-thinking

- Evenson, Shelley, Dubberly, H. “Design as learning—or “knowledge creation” — the SECI model” from ACM interactions, Volume XVIII — January + February 2011

- von Foster, H., World in Spectacular Light, London Review of Books, Vol. 46 No. 23 · 5 December 2024, https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v46/n23/hal-foster/world-in-spectacular-light. This is a book review of Robin Schuldenfrei’s Objects in Exile: Modern Art and Design across Borders 1930-60

- Google Design Sprint Website (2025) “Design Sprint Methodology.” https://designsprintkit.withgoogle.com/methodology/overview

- Gulliksen, J.; Goransson, B. Usability Design – Integrating user-centered systems design in the software development process. Tutorial at INTERACT 2003, Zurich, Switzerland, 2003

- Holtzblatt, K. (2012). Contextual design. In J. A. Jacko (Ed.), Human-computer interaction handbook (3rd ed., pp. 19). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b11963

- Horst Rittel, H. “On the Planning Crisis: Systems Analysis of the ‘First and Second Generations,’” 1972

- Interaction Design Foundation . What are UX Design Process Best Practices? https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/ux-design-processes#ux-design-process-faqs

- Interaction Design Foundation (2024) What are UX Design Process Best Practices? https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/ux-design-processes#ux-design-process-faqs

- Jacobson, Ivar; Booch, Grady; Rumbaugh, James. (1999) The Unified Software Development Process. New Jersey: Addison-Wesley.

- Jones, J. C. (1970). Design Methods: Seeds of Human Futures. Wiley.

- Mayhew, D. J. (2012). Spreadsheet tool for simple cost-benefit analyses of user experience engineering. In J. A. Jacko (Ed.), Human-computer interaction handbook (3rd ed., pp. 12). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b11963

- Mayhew, D. J. (2012). Usability + persuasiveness + graphic design = eCommerce user experience. In J. A. Jacko (Ed.), Human-computer interaction handbook (3rd ed., pp. 13). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b11963

- Mayhew, D. J., & Follansbee, T. J. (2012). User experience requirements analysis within the usability engineering lifecycle. In J. A. Jacko (Ed.), Human-computer interaction handbook (3rd ed., pp. 9). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b11963

- Mayhew, DJ (1999) The Usability Engineering Lifecycle: A Practitioner's Handbook for User Interface Design, Morgan Kaufman.

- Moholy-Nagy, L. (1947) Vision in Theobald, P Chicago, 30-32. Realization is what Moholy-Nagy calls ‘Social Biological Synthesis’

- Peart, R. (20127) Why Design is Not Problem Solving + Design Thinking Isn’t Always the Answer from AIGA Eye on Design, January 19th, 2017 https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/why-design-is-not-problem-solving-design-thinking-isnt-always-the-answer/

- Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169

- Rosenberg, D. (2020) UX Magic, Interaction Design Foundation

- Rosson, M. B. and Carroll, J., Usability Engineering: Scenario-Based Development of Human-Computer Interaction Morgan Kaufman, 2002

- Rosson, M. B., & Carroll, J. M. (2012). Scenario-based design. In J. A. Jacko (Ed.), Human-computer interaction handbook (3rd ed., pp. 20). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b11963

- Schön, D. (1984) The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Acton, Routledge Press, New York

- Shanks, M. (2022) An Introduction to Design Thinking, Process Guide, from Stanford Business School https://web.stanford.edu/~mshanks/MichaelShanks/files/509554.pdf

- Simon, H. A. (1969). The Sciences of the Artificial. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

- The 6 Steps of the Design Thinking Process, IDEO Website accessed on 5 January 2025 at https://www.ideou.com/blogs/inspiration/design-thinking-process?srsltid=AfmBOop-CfwQVih5_qooOG1svrgnByGUAF4EZvpaz9JRwTlNlP2E6-tb

- Winograd, T., Bringing Design to Software, 1996

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge just a brief list of design professionals with whom I have been privileged to work and have influenced and inspired me in my design work:

Michael Arent, Hugh Dubberly, David Siegel, Iwan Cuijpers, Richard Anderson, Susan Dray, Daniel Rosenberg, Elizabeth Dykstra-Erickson, David Zeidman, Ruurd Priester, Nico ten Hoor, Gert van der Meulen, Jose Arcellana, Patrick Larvie, Irene Au, Nico MacDonald, Marilyn Tremaine, Wendy Mackay, Robert Jacobs and most recently Anna Wildeman and Laura Chavarria.