In the last blog post, I traced the historical evolution of design processes as well as other references contributing to the timeless foundations and the sources underlying the Timeless Scalable Design Process.

The journey began with early design pioneers like László Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus, and continued as two professional strains: HCI and Design converged to create a new discipline and new processes. By synthesizing all these insights from nearly a century of design theory and practice, I came up with the process we covered in blogs 1-3. At the end of that post, I also named the resources and the source materials for much of what you find in these blog posts.

Part 5: The Process in Action

From an extensive overview of historical design theory in my previous post, we now turn to design practice.

"Think of the design process as involving first the generation of alternatives and then the testing of these alternatives against a whole array of requirements and restraints." - Herbert Simon

Managing a design process: Phase Names

First, let’s focus on an example of how this design process is managed in a typical project. The focus here is demystifying the design process to non-designers as well as giving a best practice in design for the design community.

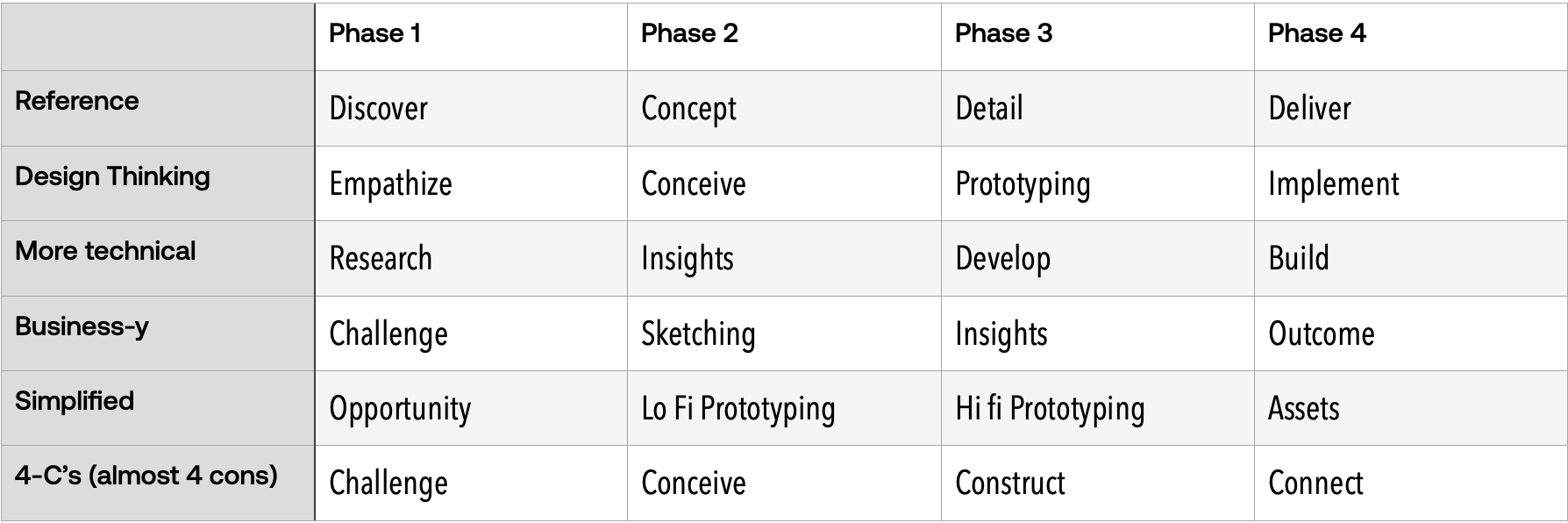

First thing I wanted to address is the naming conventions of the steps themselves. It is important to understand the general function of the design process phases. To that end, there are labels for each step that do their best to describe what happens during these phases:

- Discover — exploring and defining the design challenge

- Concept — concepting and defining the solution to the design challenge

- Detail — creating a detailed design from the conceptual design

- Deliver — creating and delivering assets iteratively with engineering and other stakeholders.

These labels are meant to be as accurate as possible. And I have worked very hard to make these generalizable titles good in almost any situation. However, in general, whenever anyone (or any group) endeavors to make anything universally applicable, they inevitably end up with something intensely personal. So it is important to empower designers to customize these phase names to fit the group with whom you are designing.

A couple of terms before you go

For the purposes of this article and especially for an agreed vocabulary for talking about the phases, the following definitions apply. These are not to say semantically pure definitions, but an explanation as to how I use the words and allow you to translate them into terms of your own understanding.

Goals — a universal goal for a phase in a project (e.g. “reframing the problem” during Discover and “conceptual design” during Concept).

Deliverable — the document or design artifact or otherwise a noun that will address one or more of the goals, (e.g. a problem statement in Discover, or a prototype in Concept) .

Activity — the method or technique or otherwise a verb that will address one or more of the deliverables, (e.g. an action can be a simple deed like a conversation with a product manager).

Method — a mini-process where techniques and deliverables are combined, e.g. scenario-based design is a research method for delivering end-user requirements.

Technique — A design activity generic or specific flavor. E.g a usability test vs a formative usability test. A more generic term would mean something to a non-designer than the specific would. Likewise a more specialized term gives more direction to a designer as yo what they will do.

Phase Naming conventions

The far easiest route is to just use the names discussed here for the reasons they function as described above; not because these names are perfect but because they are there and a discussion of what names to call these phases can easily degenerate into a religious war consisting of an untangleable mix of semantics, tastes, and preferences. One person’s truth is another man’s fiction. The same is true when naming the steps in the process.

But if you are determined to open that pandora’s box and strike out on your own for your custom names then let’s start by acknowledging some very valid reasons for braving this storm.

There are good reasons to come up with different names for the phases. For example, it could be that the name of one of the phases has a completely different meaning in a particular company or domain. For example, in the 60s, it was common for designers to refer to a detailed phase a “programming” phase. Now that design occurs in the context of software, that term is inappropriate and misleading.

Other reasons can be: Speaker and listener factors can also play a role as the intended meaning and interpreted meaning can differ based on individual knowledge, experiences, and assumptions. Pragmatic influences may also need to be taken into consideration, e.g. what something means often depends heavily on why it's being said, not just the literal semantic content. Cultural stumbling blocks and shared understanding or other terms can be reasons to change the names, as is the odd chance that someone had a parent like a designer version of Frank Zappa and named their kid “Concept,” who is now the lead developer in the project.

But before jumping into an involved discussion on naming conventions, when it comes to labels, I would rather throw an opinionated but sincere stakeholder a bone and change the names, as long as it does not change the goals of the phase. The goals in those phases comprise the backbone of design not what you call them. Achieving these goals in different activities can make the process bend (or what I call scale), but ignoring a goal altogether makes the process break from a designer’s standpoint.

It is also important to keep in mind when you change one term it may effect the meaning and understanding of the others. Consequently, when changing names use terms that work together as a family or concept. Here are some alternative names that, for better or worse, have been used by other design agencies, designers, and pundits (the names have removed to protect other people like me):

And this list could go on. You can also come up with all sorts of perfectly valid value judgements if one of the above sets is better or worse; because, there is no one true semantic. A semantic depends on a shared reference base. In other words, there is no true naming—only true agreement on naming. It must also be said that as long as a single shared base reference is the design rationale for all the names of the phases, then the resulting names should be both understandable and conceptually unified. In other words, semantics is the art of making the arbitrary feel inevitable.

Or to quote Lewis Carroll from “Alice Through the Looking Glass,” with Humpty Dumpty speaking for a an entire design team:

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master——that’s all.”

Extending/Dividing the Phases

The steps are designed to sequentially follow one after the other. For example, no one can start the Concept phase without knowing the problem they were solving, as established in the prior phases. Nor can you detail design without a concept, unless you like taste wars and ineffectual software. To be clear, reordering the steps makes no sense and is not recommended for professional results (for an example of what such a project looks like see this educational Buster Keaton film: https://youtu.be/Xd6ddOlbKp8?feature=shared .

Still the question arises about extending or dividing the steps.

Extending the phases

By extending phases, I mean adding non-design activities and goals to the project. This helps create unified project plans and coordinate dependent activities. When adding goals, separate them clearly—design goals vs. engineering vs. marketing—to clarify each team's work without creating competing priorities. This approach makes design priorities clear to other stakeholders and helps when non-designers propose ideas already covered in design goals but using different terminology. It also coordinates design efforts with other stakeholders' work, informing the design team and eliminating duplicated effort.

However, one thing to look out for, not that this often happens, is when you are designing in a hostile environment (e.g. when a stakeholder is against using design and it is imposed on them), some people with less honorable intentions might attempt to schedule goals to replace your own. It is important not to negotiate the goals. The tools or methods can be negotiated for any number of valid reasons, but not the goals; they always remain key to good design.

Dividing the phases

With or without adding goals, it is possible to subdivide the steps into any number of subcategories. Six or seven-step processes are common. Bruce Archer, for example, broke his academic design process down into 239-steps.

It’s all a matter of what is the smallest number of phases required. Let’s say there will be a large formal research effort that will start and end in between phases 1 and 2. And that phase needs to be managed in isolation of the others. Then that would be a compelling reason to add an extra step to include that step alone. In general, 4-9 steps is probably large enough to handle even the most complex projects. The main important factor is the integrity of Discover - Concept - Develop - Deliver is left intact. In other words, the goals and their dependencies on the previous steps are maintained. Back to our research effort example, the project naming could look like this:

Discover - Research Effort- Define - Develop - Deliver

But from the 4 step perspective it is:

Discover - Define 1 (Research Effort) - Define 2 (Other Define phase goals) - Develop - Deliver

When splitting a phase it is important to make sure inter-dependent activities are added to the correct split phase section. With this in mind, splitting the steps is entirely possible, but whether it is necessary or not depends on the project or the method involved.

Managing the design process

Managing the process is essential to a good design. Let’s be clear this is not design management, it's process management that’s completely different, I refer here purely to the management of the design activities and deliverables which makes a small but essential part of design management. The management of the process must support the iterative nature of design, in other words the ability to revisit or even retrace your steps based on new learning.

This process management also makes the design process explicit and transparent, less obscure to the non-designers. This process management also should support process shortcuts: how the process can bend without breaking. An example of a process shortcut would be reducing the research efforts to something that takes less time in order due to a new time constraint. But in so doing, by making explicit the changes or sacrifices in activities or deliverables in the design process, you can also make clear the increased risk that is inherent with doing a project change in mid-flight.

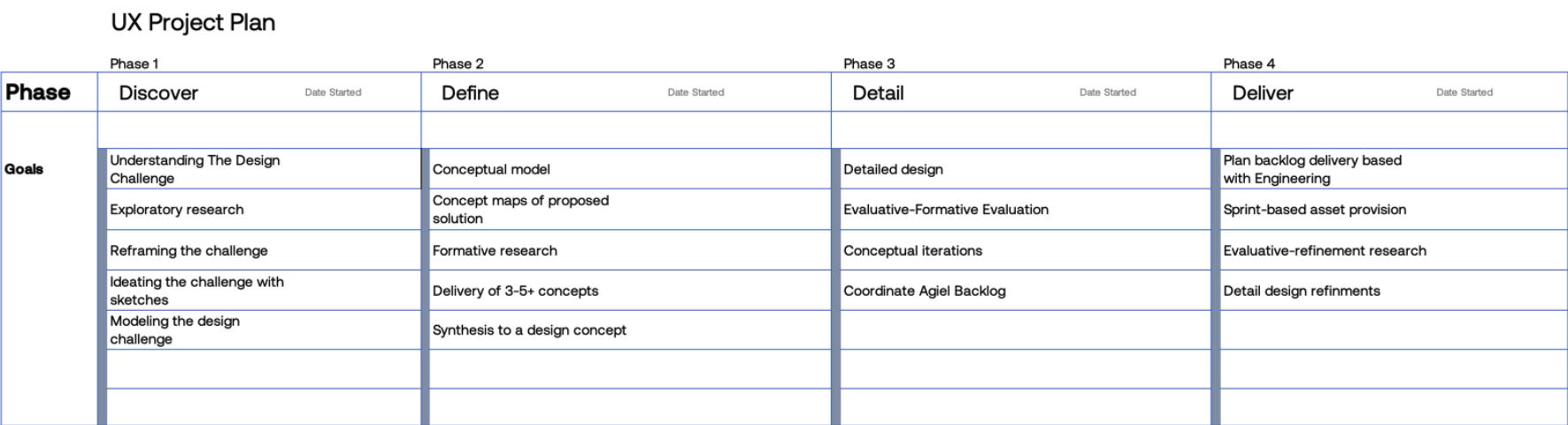

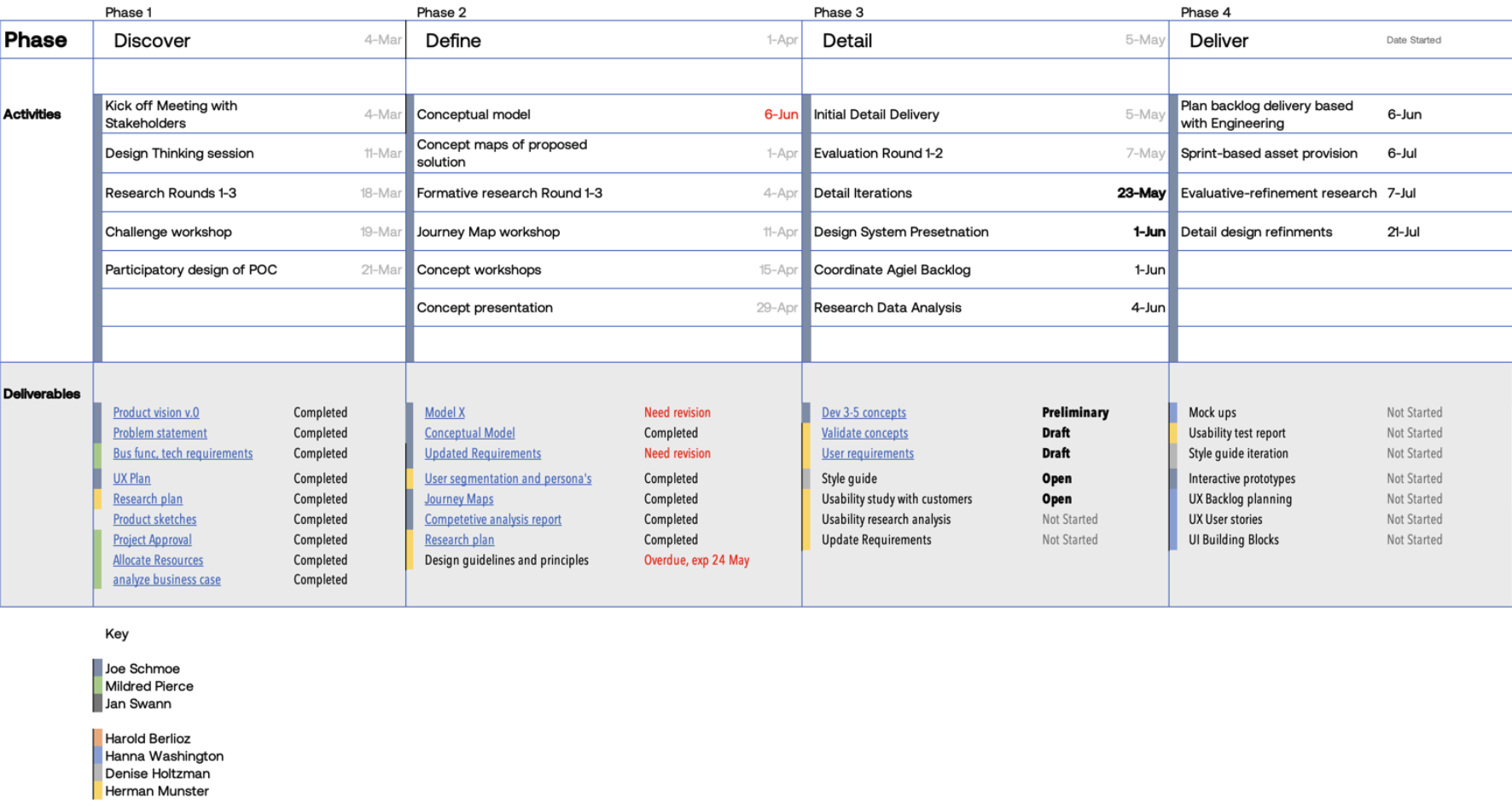

To help manage the design process I recommend a structure, most easily expressed in a table structure. A table structure that can grow with the project into several parallel functions as it goes through different iterations:

- Design Project reference for client and internal team

- Project design tool

- Project proposal tool

- Design learning tool

- Project tracking tool

- Design and Project reference

Before going into details of each version of this tool, I want to point out that I am showing a table version purely to make the over all structure clear without resorting to an explanation of database structures and other technical elements. This table can easily be implemented in Apple’s Numbers, Excel or other spreadsheet. But it is even more powerful when it has some database functionality behind it and/or integrated into an existing design infrastructure such as Miro, Jira, Slack, GitHub, etc.

Design Project reference

At its simplest level, the table starts out as a table with a column for each phase and a list of goals for each phase. This document alone is a great way to orient both a team and a client into what to expect in the design process. The discussion of high-level goals is also an opportunity for stakeholders to add any additional goals that are essential for this particular project.

The document is also a talking point specifically to a client, as a kind of design bill of rights: something a client or team lead can use to hold design accountable to achieve all the necessary goals of a project.

Project design tool

Another iteration on this project is when you add a list of activities and deliverables to each phase. The project plan can be guided by linking a deliverable to a goal. This link will determine in which phase a deliverable is due. Likewise, if you also link activities to a deliverable, then the activity once selected can also have a due date by the end of the phase. With the use of linked lists or a database, it is possible to filter the list of activities based on the selected deliverables, helping the designer pick the right activities for a deliverable but also select activities they had not considered or maybe even knew about. A linked list can attach a number of days’ duration or resource hours to the selected activities. The total activities in a phase can give you a duration and rough estimate of the project. This can guide the designer in coming up with a budget and scope for the project that can be the basis for a project plan.

Project proposal tool

Once a designer has finished designing their design process, they can add a start date to the activities. They can start by establishing a start date (a specific date or a “week 0” start) and then create a start date for the first activity, usually a project kick-off, and then setting the start of the next activity based on the duration of the previous activity. This does not automatically generate a project plan as a designer will want to analyze and decide whether an activity will take the suggested length or if the context of the plan will require less or more time. For example, a kick-off meeting can be a 2-hour meeting in many cases, but for real complex problems, it could take half a day, or even be combined with other activities, like a product innovation workshop. Another example is the time it takes to schedule users for a usability test. If the design team has ready access to users, like with an internal team of users, the scheduling can take days; on the other hand, for users that are spread out geographically and hard to contact, the recruitment process could take weeks. Analyzing these variables then helps the designer estimate the correct amount of time. Moreover, a designer may also decide to add some contingency timing to an activity to account for possible delays—particularly important for a fixed project schedule.

Once these determinations are completed, the result is a project proposal ready to be re-negotiated with some stakeholders, and then costed out and presented or sent to the decision-making stakeholders.

Design learning tool

As already mentioned, a designer can discover new design methods and activities with a list of activities. This is especially helpful if there is a link to the phase goals and the activities/deliverables; but not necessary especially for the more experienced designer who already knows these things off the top of their head.

However, no designer, even those with thirty plus years of experience, knows it all. There can be design activities that can be more effective than the ones he knows about.

By keeping a list of activities that everyone in the staff knows about can help a design explore and learn new methods. Likewise, a designer or design operations person could also maintain a link of new and interesting activities or deliverables, so the designer can also explore new methods or techniques they hadn’t tried before. They can follow these links and explore learning opportunities or examples for a new method.

However, a real extra advantage to the list of activities can be if it includes a name or names of employees who know a given method. This kind of list, or for a large company, a database, is very handy to inform the designer of the many different methods, techniques, deliverables there are to achieve the same goal.

The designer can analyze the project context and custom tailor the selection of methods to the context. However, the real advantage of such a database is also to discover new internal methods or techniques that the designer is unfamiliar with, which can solve a project problem they don’t know how to solve.

For example, let’s say that a designer is relying on a usability test to evaluate a prototype. But they do not have enough time for a formal usability test or even a ‘guerrilla’ usability test.

If they look for how the same goal can be achieved, they can come across someone else’s technique that uses much less time with an acceptable associated level of risk. With the person’s name associated with it, they can contact that person who can either train or mentor them, or even be added to the project for that activity.

In this way, the design learns more about new methods or deliverables they don’t know but a colleague is specialized in.

Project tracking tool

Once a project proposal is accepted and begins, assign firm dates and lead resources responsible for each activity or deliverable. Place dates on the line with each item along with the assigned resources.

Design projects are iterative—completed phases sometimes need revisiting when deliverables become outdated due to new information. Track these iterations using typography: use red text for new dates when work must be redone, then change back to gray when completed.

Manage whether deliverables actually address expected goals by including goal lists in each phase header. Check off completed goals and supplement incomplete ones with supporting deliverables.

Moreover, given the ubiquitous linking facility available in almost any tool, deliverables and activity artifacts can easily be linked, making it easy to keep track of project deliverables.

Project deliverables are usually uploaded to a commonly accessible cloud storage directory. But by linking these deliverables and activities, one does not need to know where the file is kept; they have single-click access to it, via this document.

The deliverable link could take the user directly to the deliverable and open it. An activity link, or deliverable link where there are multiple artifacts, can take the user directly to the directory with all the documents needed for an activity, e.g. the testing script for the test as well as session transcripts, videos, etc.

Almost all of these collaborative documents have some simple role-based restrictions, so some users could have only read-only access to the document so they can click links but not change the project tracking. Moreover, when a non-editor sees the document, they can see the current status of the project in a single glance and tell the project manager of any updates they have missed: for example, a just-completed activity to a rejected deliverable.

Design and Project Reference

When the project is complete, one can review what activities or deliverables are best practices to follow. It only remains to call out which ones of the deliverables are best practice (and perhaps also using a commenting facility to mention what worked and what didn’t).

You can compile these lessons learned or best practices into a single area in your design infrastructure. If you maintain a page for a specific activity or deliverable, you can add project links to act as additional examples. E.g. a page dedicated to usability tests could include its test script that was particularly effective.

===

In the next article we cover a specialization on the Timeless Scalable Design Process, developed at Keen Design, called Value-Driven Design (VDD). This is a design framework that shifts focus from building specific features to delivering measurable value to all stakeholders in a product's value network (organization, business, customer, end user, etc.).